One of my historically weaker areas of knowledge within the realm of hypermobility and connective tissue disorder has been my understanding beyond the confines of HSD/hEDS.

This year I have seen a coincidentally higher number of patients coming in asking for formal assessment on their own personal suspicions of hEDS underlying their issues, so I have had more opportunities than usual to try my hand at working my way through the hEDS 2017 Diagnostic Criteria.

What I’ve found is that ‘Feature C’ (The part of the criteria where you have to rule out or establish insufficient suspicion of any other conditions) is a pretty deep and complex criteria to fulfil. Establishing when it is indicated to refer out to external specialists to rule out other HDCTs has been no mean feat to try and figure out.

Luckily, I work in a team where one of the higher ups is a hypermobility specialist that works within a dedicated diagnostic pathway with MDT input, so I’ve not had to tackle this challenge myself. I simply complete as much of the criteria as I myself am able to complete competently within my scope, and then refer these patients in that direction so they can get the care they need.

Nonetheless, I’ve found myself wanting to know more about the process, to reinforce my knowledge base in the area.

To my mind, given that HSD/hEDS may actually be the most common connective tissue disorder(s) at a recently proposed prevalence of up to 1 in 500, it would not make sense to have to routinely refer on every single suspected hEDS case to a geneticist, rheumatologist and cardiologist to rule out every other (much rarer) connective tissue disorder or disease associated with joint hypermobility in order to diagnose it once the other criteria are fulfilled. That would feel similar to routinely doing an urgent full spinal MRI every time a patient came in with back pain (regardless of the presence or absence of any other clinical features), to rule out bony metastases, axial spondyloarthropathy and cauda equina syndrome before you could ever diagnose a single case of non-specific mechanical low back pain.

Like every other scenario of this nature within the diagnostic realm, we have the concept of “Index of Suspicion” coming in to save the day, where the presence or absence of certain clinical signs will raise or lower the suspicion of certain underlying conditions. This then guides the process of whether there is any reasonable suspicion of these red flag conditions, and therefore whether they need to be explicitly ruled out or not via onward referral.

It has been this month that I’ve been looking for a resource to help with clinically reasoning the relative level of suspicion of the rarer HDCTs in the process of assessing for hEDS. Ideally it would be something relatively quick, to enable it to fit into an already time-strained consultation where most likely, other things need to be covered as well. Something like ‘bladder and bowel changes, saddle anaesthesia and sexual dysfunction’ for Cauda Equina, or like SCREEND’EM for spondyloarthropathy.

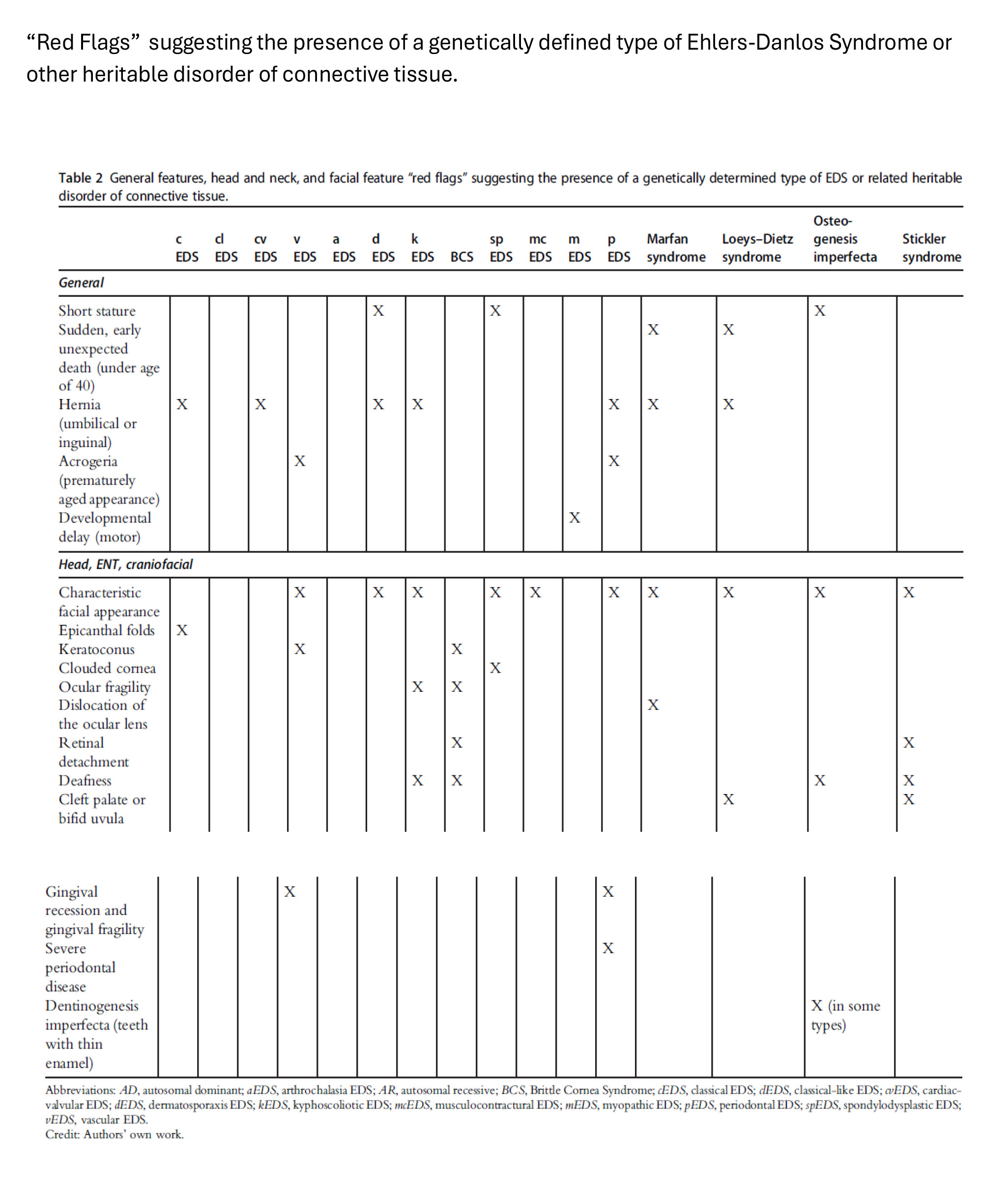

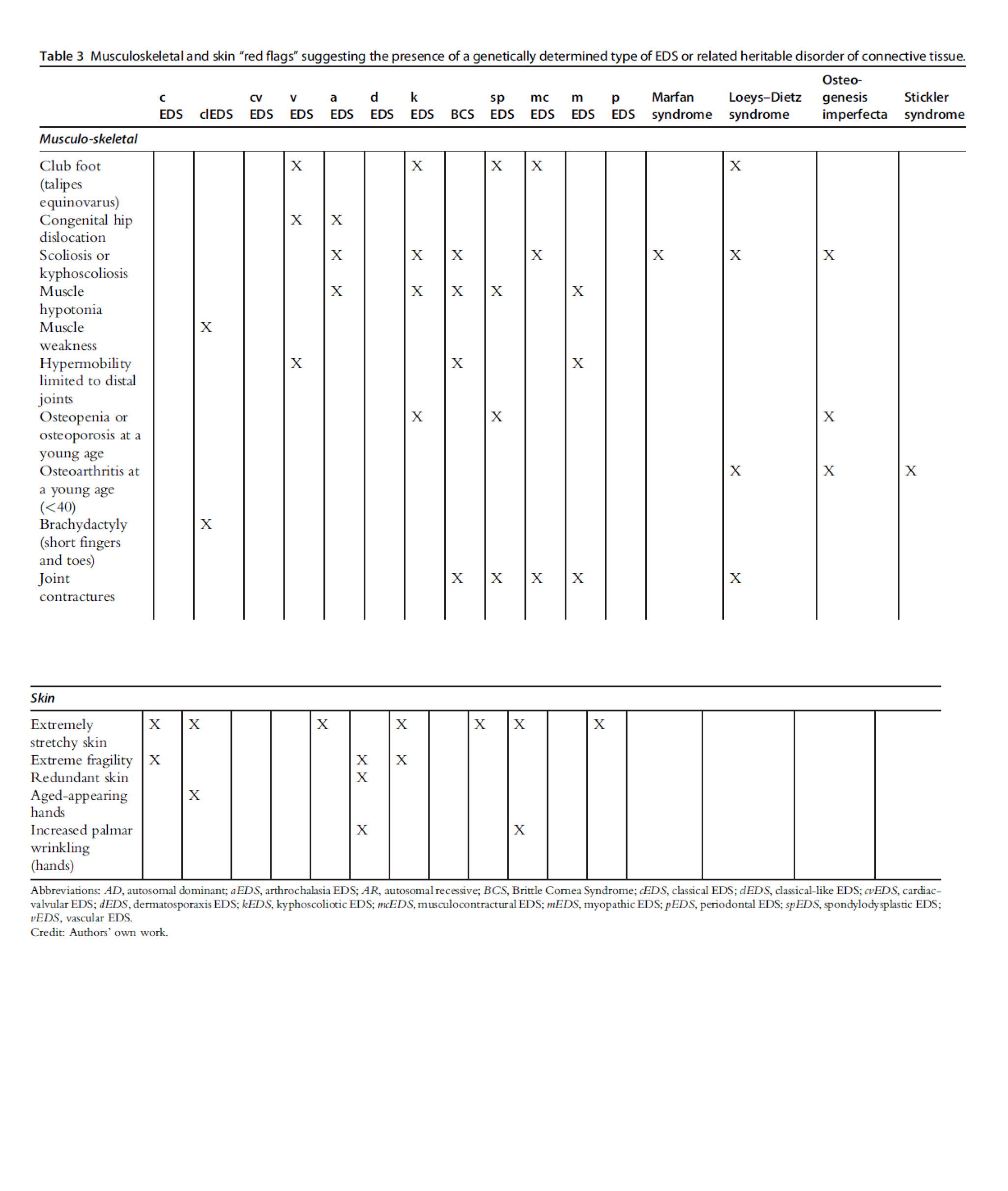

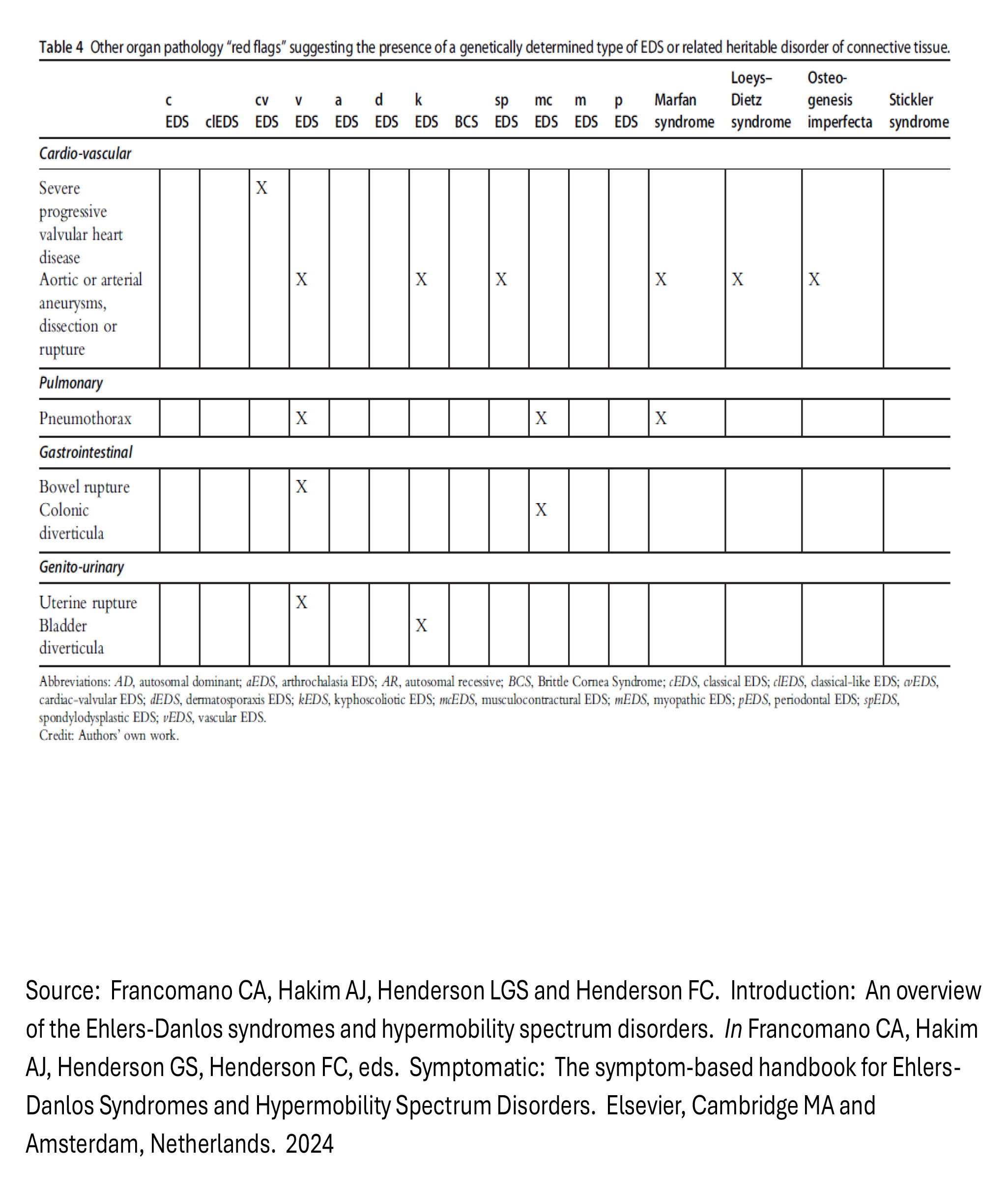

One excellent resource I found was a table that comes from the book “Symptomatic: The symptom-based handbook for Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes and Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders” by Dr. Clair Francomano and Dr. Alan Hakim, this was posted as an additional resource on the Bendy Bodies Podcast

Quite conveniently, it was almost exactly what I was looking for. A list of features that raise suspicion of the rarer subtypes of EDS and the other most common HDCTs.

Here is that very (set of) table(s).

For those of you that just want the primary source material, then there you have it! Digest that information at your leisure, and I hope it aids your clinical reasoning in your next encounter with a patient or client with a suspected HDCT.

Designing a Modified Version for Clinical Reasoning

Personally, I found the visual formatting of the above table challenging to parse and wanted something a little clearer to look at. This then turned into a multi-stage process of experimental modification of this table as I continued tweaking the visualisation of the information further and further into something that could be usable at the quickest possible glance, mid-consultation.

Be forewarned, the following stages of modification/experimentation I’ve documented below are far from a rigorous or academic process. Do not mistake this for the development of an actual, validated clinical screening tool. I would not recommend relying on anything in this article as part of the diagnostic process, if you are in a position to do professionally. The content below is more of an intellectual exercise mixed with a flight of fancy in the process of trying to learn more about the rarer HDCTs, that I’ve decided to share incase other people found it helpful or interesting.

Here is the first stage of that process, where I kept the content exactly as it is shown above, but made it more clearly laid out, to remove the ambiguity about which ‘X’ belonged where.

![[HDCT Red Flags (Original Order; Reformatted).pdf]]

This was much more satisfying to look at, but ultimately still was far too visually busy to quickly digest. If I wanted this table to be something usable to efficiently clinically reason with in a consultation, I’d have to continue tweaking with it. Particularly where a clinical feature was shared by many conditions in the table, I wanted a better way of telling which conditions I should be more or less suspicious of in the presence of such a feature.

I could not (and still can not) see any particular pattern explaining the order of columns in the original table besides “put all the EDS subtypes first, and then the 4 non-EDS conditions at the end”. As a result, I decided to see what it would look like if I put them in order of disease prevalence:

![[HDCT Red Flags (Ordered by Prevalence).pdf]]

This was immediately much clearer because it allows you to see at a glance which conditions were more or less suspicious in the presence of any specific clinical feature. More likely towards the left, less likely towards the right!

With all the prevalence values laid out like that, I realised that having the rarer subtypes of EDS in this table was a great show of completeness, but it negatively impacted the visual efficiency of it as a clinical reasoning tool. I thought I would create a separate version that excluded the ultra rare “less than 200 recorded cases” subtypes (and any of the feature rows that only applied to those ultra-rare subtypes), as it feels they added disproportionately more cognitive load relative to the benefit they added from a clinical reasoning perspective due to the unfathomably low likelihood of ever being able to use the information:

![[Top 6 HDCTs Red Flags (Ordered by Prevalence).pdf]]

This was finally the point at which this started to look like something that could go on a clinic wall, or that you could pull up quickly on a computer during a consultation, and actually use!

What I felt was missing now was a way to pick out the ‘heavy hitter’ clinical signs (The ones that only applied to one of the 6 conditions). That way, you know if it is present that it’s clearly pointing in one direction and not another. I also wanted a way to separate out the ’true’ red flags, (the ones that were actually a sign of serious danger to life, the ones that are sufficient on their own to hit your threshold of suspicion to refer out, without the presence of any others).

As a result, I highlighted all the features which only apply to one condition in yellow, and then all the features that could be an imminent threat to life in dark red. Finally, I wanted to experiment with grouping these together. One section for the Big Crimson Banners (High risk to life), one section for the features that were unique among the 6, and a final section for the features that were shared among one or more. The result was this:

![[Top 6 HDCTs – Red Flags, Stratified by Specificity and Urgency.pdf]]

Assuming this were the definitive totality of potentially relevant clinical signs for each of these conditions (or at least a confirmed list of the most significant), I think this formatting and arrangement lends itself really well to a quick visual evaluation of the relative urgency, weight and specificity of the different features to your suspicion of a given condition.

It especially highlights some really interesting things that were NOT immediately apparent on first glance to the original table. For example, the presence of bladder and uterine rupture in a patient already meeting the other criteria for hEDS are pretty clear signs to refer out immediately on a pretty high suspicion vEDS. Not only are they high risk but they’re also only a suspicious feature for vEDS, which means there’s very little ambiguity about what concerns you should be having in that case.

Similarly, if you were to see a patient meeting the hEDS criteria with a history of pneumothorax, that pretty immediately points you in a suspected direction that the original table did not.

The only problem is that I am not so sure that it DOES represent the definitive totality of potentially clinically relevant signs. For Marfan Syndrome, for example, a number of the items on the Revised Ghent Criteria are absent from the original table. Given that’s the case, then it is not unreasonable to suspect that other very relevant features for the other conditions may also be absent.

As a result, I’m not going to treat the final Frankenstein’d version of this table as a complete and definitive source of red flags for these HDCTs, but my journey of modifying it was an interesting intellectual exercise in understanding these flags better, and I may in future develop and add onto this table as my knowledge of these conditions evolves, to act as a clinical reasoning aide memoire (for personal use of course, as I’m not nearly arrogant enough to assume I’d be able to make a robust, valid screening tool for wider use with a process as simple and un-academic as I’ve just done!)

Hopefully reading this blog may have inspired others to look more into this area. Maybe in many years one of us will have completed and published some real research on this topic, unveiling and validating the very screening tool we need for this purpose!

A big thank you to the authors (Hakim, Francomano, Henderson and Henderson) for the work that went into the development of the original table, and the many many years of experience that were pre-requisite to the publishing of the book itself. I have started reading it as a result of finding this table and it’s an absolute treasure trove. I may write some things in future regarding what I learn from it.